The first time I hiked between Mount Natib and Mount Mariveles, I felt like I was discovering a completely different Bataan from the one I knew as a child.

Growing up, this peninsula had always meant beach trips – I remember sitting in the back seat of our car, watching with curiosity as we wound through mountain roads before emerging at the coast. That contrast between mountains and sea seemed strange to my young mind.

It wasn’t until my thirties that I finally ventured onto these trails, becoming a frequent hiker between these dormant volcanic giants.

Now I see Bataan for what it truly is – a place where mountains meet the sea in dramatic fashion. These peaks rising straight from the coast create a landscape that’s both beautiful and unique.

The Volcanic Foundation

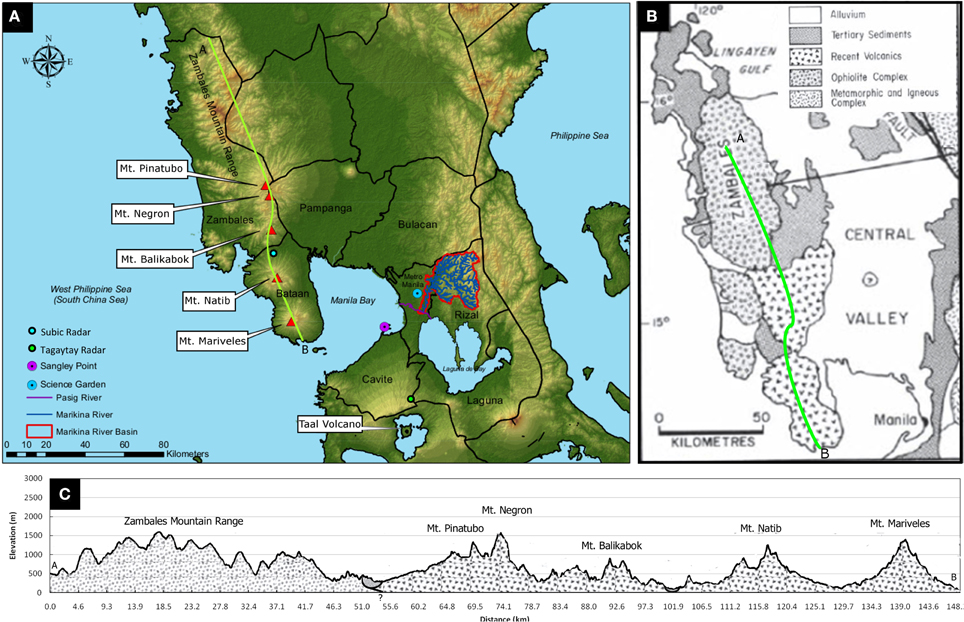

This distinctive landscape is anchored by two sleeping volcanoes: Mount Natib in the north and Mount Mariveles in the south. These ancient mountains, part of the eastern Zambales range, stand as silent witnesses to the tremendous forces that shaped the peninsula.

Naturally we’re earthquake prone too.

Bataan Peninsula sits near several active fault systems, including the Manila Trench and East Zambales Fault, making it particularly vulnerable to seismic events.

This geological reality famously led to the mothballing of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant in the 1980s – a $2.3 billion project that was completed but never fueled.

Built near Mount Natib, the plant raised serious safety concerns due to its proximity to fault lines and volcanic hazards. The abandoned facility now stands as a concrete reminder of how our region’s dynamic geology shapes not just the landscape, but also our development decisions.

Satellite images reveal lineaments – long, linear features in the landscape interpreted as active faults – with a prominent one stretching northeastward through Hermosa towards Bacolor, Pampanga.

These hidden features remind us that the landscape, despite its apparent permanence, is in constant flux.

I see evidence of these geological forces on my own property, where the land slopes dramatically – a direct result of the area’s volcanic history and ongoing tectonic activity.

What might seem like an inconvenience when gardening is actually a window into the peninsula’s geology.

The Story Written in Red Earth

The volcanic heritage of Bataan is most evident in its distinctive red-hued earth, particularly prominent in the upland areas.

This coloration, a result of iron oxidation in the volcanic parent material, is more than just an aesthetic feature – it’s a testament to centuries of geological and chemical processes.

These soils are typically rich in minerals like phosphorus, potassium, and calcium – nutrients that were locked in ancient volcanic rocks and gradually released through weathering.

I imagine that the high iron content, which gives the soil its distinctive red color, can also play a role in a permaculture garden.

In the upland areas which is characteristic of where I’m, these soils are typically compacted, with varying water infiltration rates that create unique microenvironments for plant life.

The lowland areas tell a different story.

Here, the delta plains are composed of Quaternary alluvium – consisting of consolidated silt, clay, and poorly cemented sand and gravel – speaking to the endless cycle of sediment transport from mountains to sea.

These young fluvio-marine deposits remain highly susceptible to compaction, creating a dynamic landscape that continues to evolve.

The Dance of Rivers and Tides

The peninsula’s water systems create an intricate dance between mountain and sea, with the Orani River flowing 20 kilometers from Mount Natib’s forests to Manila Bay, carrying vital minerals to the coastal plains.

Along the eastern coast, where the Pampanga, Angat, and Bulacan-Meycauayan Rivers meet the bay, a broad tidal-river delta complex forms, its daily tidal rhythm continuously shaping both the landscape and local life.

From my vantage point in the valley between Mount Natib and Mount Mariveles, I witness a different water story than the one playing out on the peninsula’s eastern shores.

Here on the western side, a complex network of streams and rivers carves through the volcanic landscape, creating a distinctive watershed pattern before rushing westward to the West Philippine sea.

Small seasonal streams cascade down both volcanic giants, converging in the valley where I live. During the monsoon months, these typically gentle waterways can transform into rushing torrents, carrying volcanic sediments and organic matter through our valley corridor.

This western drainage system, though less extensive than its eastern counterpart, has sculpted its own unique topography – creating intimate valleys and natural catchments that influence everything from local microclimates to soil composition.